Global

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008

The ancient scrolls discovered in the barren Judean Desert have for decades been a source of intrigue for archaeologists, anthropologists and theologians. We uncover some of their secrets with Dead Sea Scrolls scholar Dr Gareth Wearne.

“The scrolls are a collection of more than 900 manuscripts discovered on the north-western shore of the Dead Sea, to the east of Jerusalem, comprising our earliest biblical manuscripts as well as a number of other important theological and religious works that offer a unique insight into early Jewish worldviews and practice around the time of Jesus.”

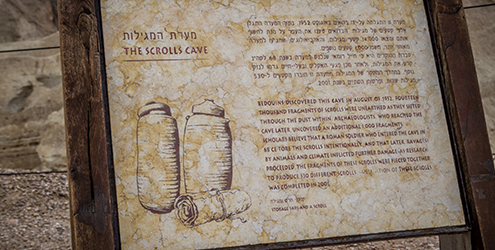

“They were discovered in 1947 when a young Bedouin shepherd was looking for a stray goat, and he cast a stone into a dark cave near what is now known as the Qumran site. He heard a jar break and went in to investigate, and inside the jar he discovered a scroll, wrapped in linen. He took it to an antiquities dealer in Jerusalem, a guy named Kando, who brought it to the attention of Archbishop Samuel, head of the Syrian Orthodox Monastery of St Mark.

Researchers at the Ecole Biblique, Hebrew University and American Schools of Oriental Research quickly realised that the scrolls were far and away the earliest biblical texts that we had … including the oldest complete copy of the Book of Isaiah.”

“The scrolls are by far the oldest biblical manuscripts ever found, and so their discovery dramatically pushed back the date of the evidence, giving us a much earlier insight into what the biblical texts looked like.

An interesting insight to come out of the scrolls was the fact that the biblical texts existed in multiple forms, and the fact that these different manuscript traditions or text types existed side by side seems to suggest there was a greater tolerance of variety in that early period than we might appreciate in our modern, highly literate textual traditions."

An archaeological site in Qumran

“There were definitely variations in the wording of the Bible, and also differences in the way these texts were used. But the scrolls also brought the realisation that in the time of Jesus and the few hundred years before that, there was no Bible.

What we had at that time was a range of authoritative texts that were used in different ways by the community … including texts that seem to have had an important and authoritative status amongst early Jewish and Christian communities, but which didn’t make it into the Bible. The scrolls offer some insight into the process by which these texts became more authoritative and how the canon that we have today took shape.”

“One figure referred to in the Dead Sea Scrolls is the Teacher of Righteousness, and some scholars have tried to connect him with James the Just, the brother of Jesus and an important figure in the early church. There have also been attempts to connect John the Baptist to the scrolls’ community.

Most scholars, however, are doubtful that there is any direct connection between the scrolls and Jesus, or the early Christian movement. But there are some interesting similarities between the theological ideas reflected in the scrolls and some of the ideas in the New Testament, which goes to show the complexity of early Jewish society and culture.

Early Christianity was a movement that emerged from within Judaism, and the ideas of early Christianity were profoundly shaped by that origin.

So the short answer is no, Jesus isn’t in the scrolls, but they still give us an insight into how the writers of the New Testament understood the life and the work of Jesus, in the context of Jewish traditions and beliefs about who the Messiah is.”

“Not yet. The texts that are written in this cryptic script are quite fragmentary, and so in many cases what they contain is not entirely clear. Although, just last month researchers at the University of Haifa managed to decipher one of these texts, which includes a 364-day calendar that is different from the dominant calendar used in the Jerusalem Temple at that time.

That calendar was used to determine religious festivals, and when you are observing major festivals like Passover on different days, that can lead to conflict and disagreements. And it seems to have been a point of contention at the time."

“Early commentators identified the inhabitants of the site at Qumran as a group known as the Essenes ... and the dominant scholarly view is that this was a remote community of Essenes who had separated themselves away from the Jerusalem Temple, probably sometime in the second century BC, as part of a dramatic schism with the Temple establishment.

Not everyone agrees with that view, however, and some have suggested Qumran may have just been a way station for people travelling through, that it could originally have been founded as a fortress guarding the north-south road through the desert along the shore of the Dead Sea, or that it might have been some sort of wealthy villa.”

“Far and away the majority of the scrolls came from Qumran Cave 4, the fourth cave to be discovered. Several hundred fragmentary manuscripts were discovered there and excavated systematically by the archaeologist Roland de Vaux, who led the team that initially worked on the site.

But those fragments were generally jumbled up and scattered, and so a lot of work was done in trying to figure out the relationship between the different fragments and piecing them together like a giant jigsaw puzzle.”

“There were a number of scrolls made available for sale in 2002 and subsequently which were bought by private collections, and these fragments have been published in recent years and a number of them appear to be forgeries.

So there’s a twofold thing going on where there’s some excitement about the possibility of a new discovery, but then also caution and a much larger discussion going on about how we respond to the problem of forgeries, and how we process that as part of the larger database.”

“Not long ago the Israeli Antiquities Authority announced that they’d work systematically through the Judean desert to see if they could find more scrolls beyond the site of Qumran, and then last year a team of archaeologists announced the discovery of another cave which they're calling Cave 12.

And in that case they discovered some jar fragments, a piece of uninscribed leather which probably belonged to a scroll, and some linen wrappings which were presumably used to wrap up and protect the scrolls. And so we’re waiting to see whether more scrolls will arise and whether other texts emerge as part of this larger re-examination.”

“Initially when the scrolls were discovered, a small editorial team was appointed to oversee the reconstruction and interpretation and publication of the scrolls, and … that was a very slow and drawn out process.

In the 1990s the rate of publication increased under the leadership of Emanuel Tov from the Hebrew University in Jerusalem. Then a few years ago there was a major collaboration between the Israel Antiquities Authority and Google, who worked together to digitise the scrolls and make high-resolution images available, so all researchers can log on and see high quality images of all of the scrolls. This unprecedented access to the whole collection means that we can begin to see connections between different texts and interpret them in different ways.”

“The scrolls help us realise that the ancient religious experience was often more complex and diverse than we sometimes tend to believe, and they challenge us to take seriously the nature of complexity and plurality within religious traditions.

They also reveal that the formation of the Bible was a process that took shape as people were using and interpreting the texts as part of their ongoing life, as they sought to understand their place in the world.

The image which emerges from the Dead Sea Scrolls is one of the vitality of scripture, as it’s part of a living and ongoing process of interpretation and reinterpretation.”

Dr Gareth Wearne is a Lecturer in Biblical Studies in ACU’s Faculty of Theology and Philosophy. He was recently awarded the Dirk Smilde Scholarship at the University of Groningen’s Qumran Institute, which is devoted to Dead Sea Scrolls research.

Learn more about studying theology at ACU.

Copyright@ Australian Catholic University 1998-2026 | ABN 15 050 192 660 CRICOS registered provider: 00004G | PRV12008